The Uncomfortable Truth Behind Most “Successful” Projects

How one fix led to collapsing roofs, a rat invasion, plague—and parachuted cats.

A stitch saves nine.

But one bad fix? It can create nine new problems.

That’s how product delivery breaks—not with a single mistake, but with a fix that doesn’t account for what’s around it.

And unfortunately, this one bad fix is often a well-intentioned decision.

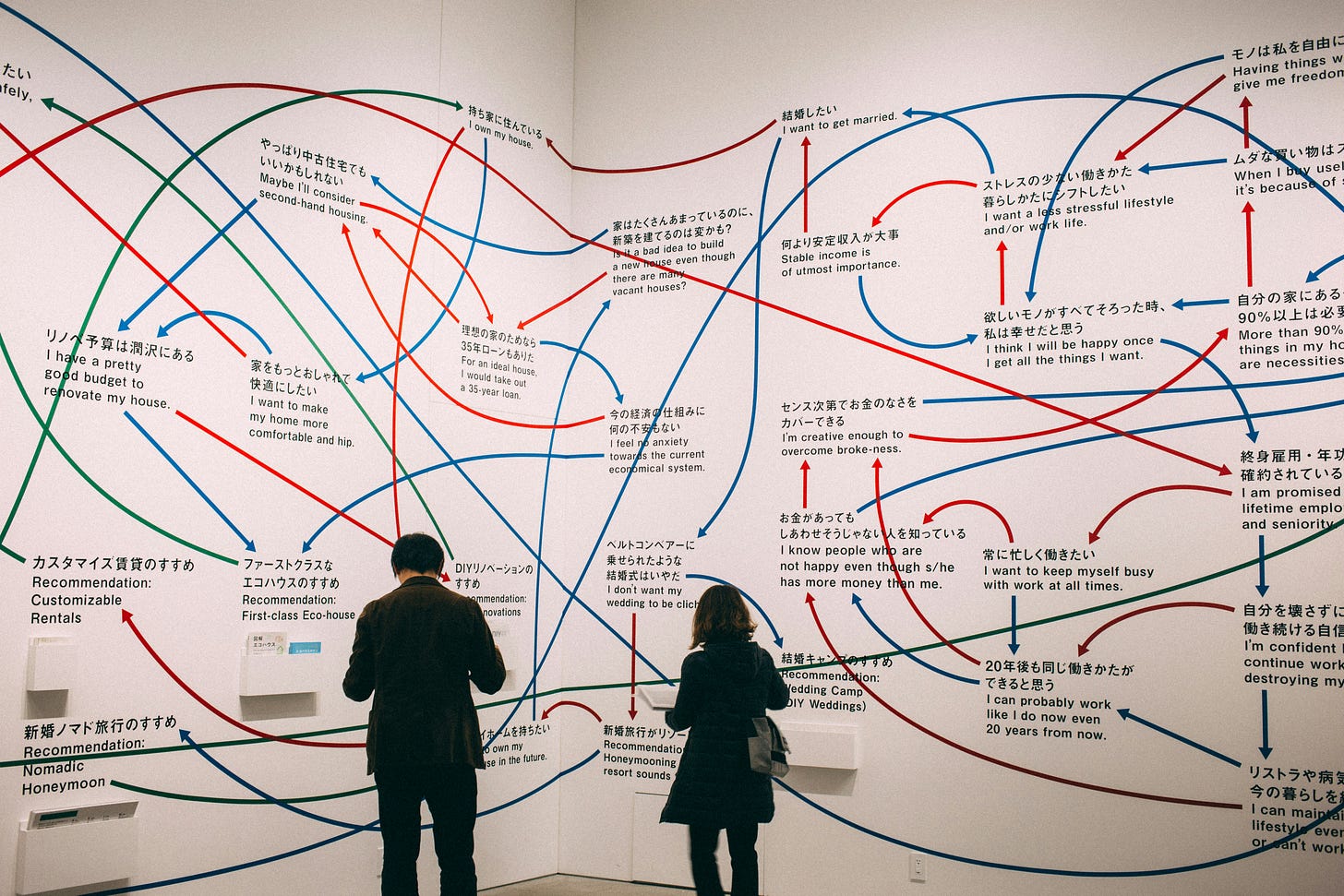

This is why systems thinking isn’t optional for delivery leaders —it’s essential.

And it’s exactly where strong program managers thrive: zooming out, looking beyond the immediate problem, and understanding how every solution becomes a new variable in a living, breathing system.

In real-world delivery, there’s never just one problem.

There’s never just one solution.

Everything is connected to something else—people, processes, incentives, capacity, context.

That’s what makes this story—from 1950s Borneo—such a perfect parable for anyone who manages programs, leads change, or steers delivery in complex environments.

The Malaria Problem That Became a Plague

In the 1950s, the Dayak people of Borneo were hit by a deadly malaria outbreak.

The World Health Organization responded with urgency.

Their fix: spray DDT across the island to kill mosquitoes and stop the disease from spreading.

It worked.

Mosquito populations plummeted. Malaria cases dropped.

From a traditional delivery lens, this looked like a textbook success.

But then the roofs began collapsing. Literally.

What Happened Next

The DDT didn’t just kill mosquitoes.

It also killed parasitic wasps—wasps that had been keeping thatch-eating caterpillars under control.

With no wasps left, the caterpillar population exploded.

Caterpillars munched through the villagers’ thatched roofs, causing widespread destruction.

But the problem didn’t stop there.

Geckos, who ate the DDT-contaminated insects, absorbed the poison.

Cats, who hunted and ate the geckos, began dying due to bioaccumulated DDT.

With the cats gone, the island’s rat population boomed.

Rats invaded grain stores, destroyed food supplies, and eventually brought with them a new disease:

Plague.

To solve the new crisis, the British Royal Air Force was called in to execute Operation Cat Drop.

They parachuted live cats into the jungle to restore ecological balance.

Yes, this really happened.

Why This Matters for Program and Delivery Leaders

On paper, the project had succeeded.

Malaria was controlled. The initial objective was met. Right?

But the solution created downstream chaos—because it was designed in isolation.

It solved the obvious problem while ignoring the systemic one.

In program management, we see this pattern all the time:

A new tool is introduced to improve “visibility”—and ends up increasing admin load while reducing trust.

A reorg is launched to speed up execution—but strips teams of autonomy and adds swirl.

A PM is brought in to add structure—but becomes a bottleneck when the system can’t absorb more process.

What looks like progress in one corner becomes pain elsewhere.

What feels like a fix becomes another fire to put out later.

The Danger of Linear Thinking in Complex Systems

Too many delivery teams rely on linear thinking:

→ Problem

→ Plan

→ Fix

→ Done

But systems don’t work like that.

They’re non-linear, dynamic, and full of hidden feedback loops. Solving one part often disturbs three others you hadn’t accounted for.

In a complex org, you’re rarely fixing a bug. You’re intervening in a living system—with dependencies, constraints, histories, and power dynamics.

Good intentions aren’t enough. Fast action isn’t enough. Even “success” isn’t enough—if it causes second-order failure.

What Great Delivery Leaders Do Differently

They don’t just execute.

They observe.

They ask, “What else is connected to this?”

They pause to consider how this decision might ripple:

→ Will this change how teams interact?

→ Will it impact morale, trust, incentives?

→ Will it shift bottlenecks instead of removing them?

They think beyond outputs.

They design for outcomes.

A Simple Lesson, a Complex Reality

The Borneo case is extreme, but the lesson is simple:

Delivery by default creates side effects.

Delivery by design considers the system.

If you’re a PM, a delivery lead, or a program manager—you are in a unique position. Not to just push work forward, but to shape how systems behave over time.

You can’t control everything. But you can ask better questions, create safer conditions, and push back against short-sighted fixes that feel good now but break things later.

The Final Fix Isn’t Always Another Tool

Borneo didn’t need another chemical.

They needed better awareness of how things were connected.

Sometimes what looks like “resistance to change” or “scope creep” is really just a system reacting to an isolated intervention.

And sometimes, when we ignore the system, we end up air-dropping cats.

Literally.

And remember: every quick fix comes with a question—what might this break?

Sounds like you are talking about the ecology of project management.